The Hidden War Between Secrets and Codes

I want to start by asking you something: How do you keep a secret in a world where someone is always listening? This question has haunted humans for thousands of years, and the answer has shaped empires, won wars, and built the internet we use today. The story of cryptography is not just about mathematics or technology. It is about the fundamental human need to communicate without being understood by those we wish to exclude.

Think about it this way. Every time you buy something online, send a private message, or access your bank account, you are relying on invisible guardians—mathematical puzzles so complex that breaking them would require more computing power than exists on Earth. This did not happen by accident. It happened because brilliant minds spent centuries figuring out how to turn secrets into locks that only the right key can open.

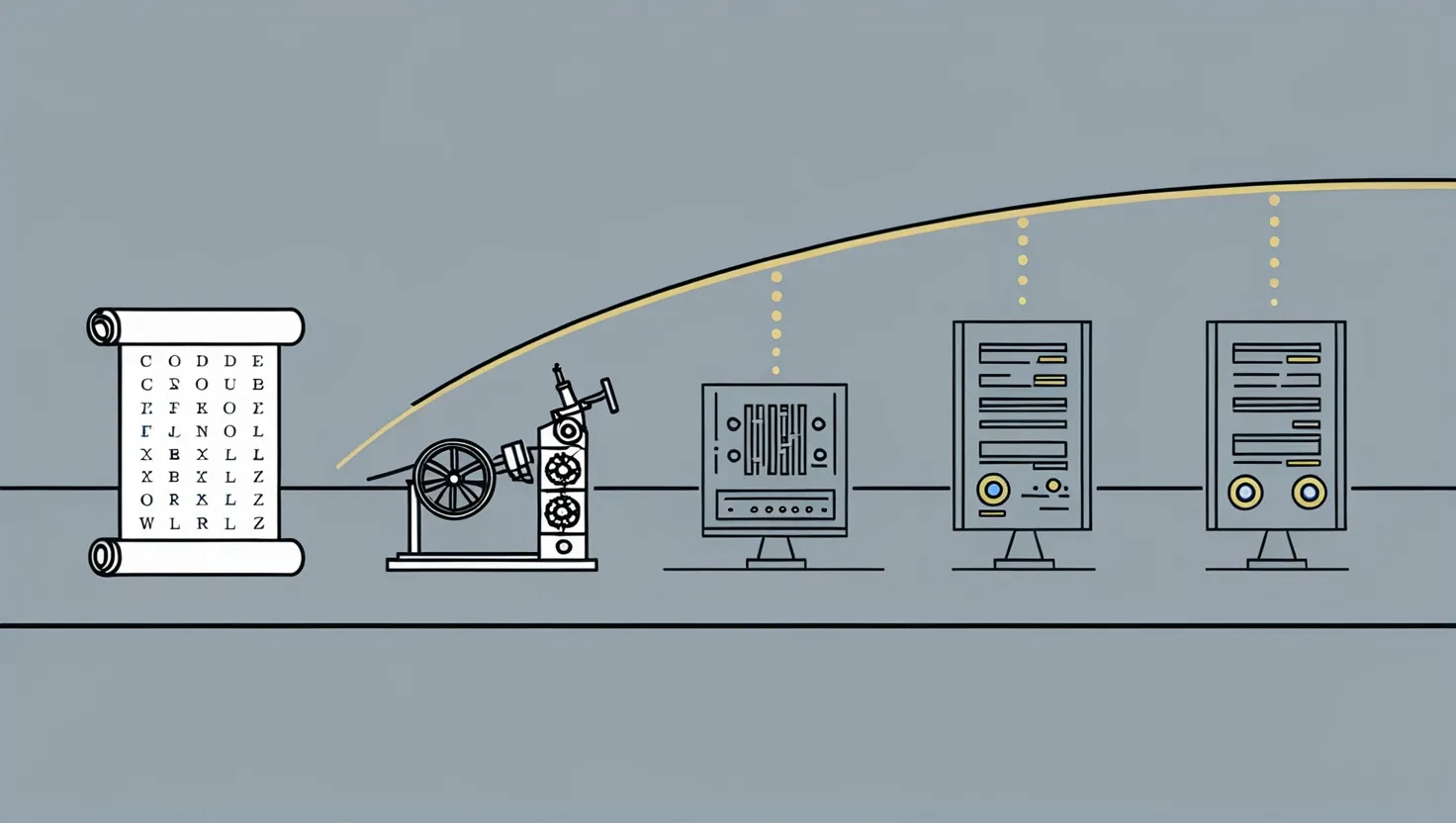

The journey from simple letter shifting to quantum physics-resistant codes is more fascinating than most people realize. It is a story filled with unexpected twists, narrow escapes, and moments where the wrong choice would have changed history. Let me walk you through the five breakthroughs that made all of this possible.

When Julius Caesar Changed How We Think About Secrets

Imagine you are a Roman general commanding troops across vast distances. You send a messenger with critical orders, but what if he is captured? Your enemy now knows your strategy. Julius Caesar faced this problem, and his solution was elegant in its simplicity. He shifted every letter in his message by a fixed number of positions in the alphabet. If the shift was three, then “A” became “D,” “B” became “E,” and so on.

Here is what made this revolutionary: Caesar did not just rely on secrecy through obscurity. He created a repeatable system, a formula that others could use. This is the seed of what we call an algorithm today. His method had a weakness, though. Once someone realized that only 25 possible shifts existed, they could try all of them. But Caesar did not care about perfect security. He cared about creating a system that regular soldiers could use quickly in the field.

What lessons do you think Caesar’s method teaches us about security? The answer is more important than you might think. It teaches us that security can never depend on people not understanding how your system works. It only works if breaking it is genuinely difficult.

For over a thousand years, Caesar’s basic idea—substitute one letter for another—remained the foundation of secret writing. Variations became more complex. People used multiple substitution rules, changed them frequently, or mixed letters in elaborate patterns. None of it was truly unbreakable, but none of it needed to be. As long as breaking the code took longer than the message remained valuable, the system worked.

The Machine That Made Hitler Feel Invincible

Fast forward to the 1920s. Technology had advanced, and with it came a new problem. Handwritten substitution ciphers were too slow for modern warfare and commerce. The answer was the Enigma machine, a typewriter-like device that looked deceptively simple but hid incredible complexity inside.

When you typed a letter on an Enigma machine, it passed through rotating wheels called rotors. Each rotor scrambled the letter differently. After passing through all three rotors, the letter bounced off a mirror-like reflector and traveled back through the rotors a different path, emerging as a completely different letter. The genius part? After each letter was encoded, the rotors shifted position slightly. This meant the same letter would be encoded differently depending on where it appeared in the message.

The Nazi military relied on Enigma with absolute confidence. The machine had approximately 158 quintillion possible settings. A quintillion is a number so large that even saying it out loud takes time. Hitler’s generals believed that breaking Enigma was mathematically impossible. They were wrong.

Polish mathematicians cracked the first version before World War II even began. They realized that Enigma had a flaw: the machines never encoded a letter as itself. If you sent an “A,” it would never come out as “A.” This single constraint gave them enough information to reverse-engineer the machine. Later, at the British facility Bletchley Park, teams led by mathematician Alan Turing pushed further. They built machines—early computers in all but name—that could test thousands of Enigma settings per minute.

Here is the part of history that rarely gets discussed: the breaking of Enigma was not a Hollywood moment where one person had one brilliant idea. It was continuous work, constant refinement, and desperate improvisation. The Allies never broke every Enigma message, but they broke enough to gain a strategic advantage that historians credit with shortening World War II and saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

“The only thing two intelligent people can reliably communicate to each other through an encrypted channel is the fact that they have been communicating.” This quote, misattributed to various cryptographers but representing their collective wisdom, captures what experts had learned: even perfect encryption does not solve every problem.

When Cryptography Became Public and Democratic

For centuries, cryptography was the exclusive domain of governments and militaries. Secret agencies developed their own systems, kept them hidden, and competed for advantage. Then something unexpected happened.

In 1977, the United States government published the Data Encryption Standard, or DES. They actually published it. They showed everyone exactly how it worked. This was revolutionary and deeply controversial at the time. Surely, critics argued, revealing your cryptographic system would destroy its security. How could you keep anything secret if everyone knew the method?

But the truth was the opposite. DES used a 56-bit key—imagine a lock that could be set in 72 quadrillion different ways. Even if someone knew exactly how the machine worked, they still faced an impossible brute-force problem. To decode a message without the key, they would need to try all 72 quadrillion possibilities. In 1977, even the most powerful computers in the world could not do this in any reasonable timeframe.

What made DES truly important was not its strength alone. It was that independent researchers, academics, and cryptographers worldwide could now analyze it, test it, and verify its security. This transparency became the new standard for cryptography. A cipher that the entire world scrutinized and could not break was more trustworthy than a secret system that only a few people understood.

Do you see how this changed the nature of trust? Instead of saying “trust us, our system is secure,” governments could now say “we published our system; thousands of smart people have tried to break it; it still stands. Therefore, it is secure.”

DES protected financial transactions, medical records, and government communications for over two decades. When it finally became vulnerable to faster computers, it was retired with honor and replaced by stronger successors, AES among them.

The Problem That Seemed Impossible to Solve

Up until 1976, cryptography had a fatal flaw. Before two parties could communicate securely, they first had to meet in person to exchange a secret key. If Alice wanted to send a message to Bob, she had to give him a special code in advance. If Bob wanted to send her a message, he needed a different special code. In a world with millions of people wanting to communicate securely with millions of others, this was impractical.

Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman looked at this problem and asked a question that seemed to have a negative answer: Could two people establish a secure communication channel without ever having met or shared a secret?

Their answer was yes, using a concept called public-key cryptography.

Here is the basic idea, stripped down to its simplest form: Imagine a combination lock. Alice publishes the combination to her lock in a public directory. Anyone can lock something in her box. But only she has the key to open it. Now Bob can use Alice’s public combination to lock his message in the box. She receives it and uses her private key to open it. The reverse works the same way with Bob’s public lock and private key.

In the real mathematical version, the “locks” are based on problems so difficult that finding the answer by guessing is practically impossible. The most famous example uses something called the prime factorization problem. Multiplying two very large prime numbers together is easy. Finding those original prime numbers when you only have the product is devastatingly hard. A modern computer cannot do this in reasonable time if the numbers are large enough.

This breakthrough made the internet as we know it possible. Without public-key cryptography, e-commerce would not exist. Every secure website connection relies on it. Digital signatures, which prove that a message came from a specific person, are impossible without it. The entire foundation of digital trust rests on Diffie and Hellman’s insight.

The Threat That Has Not Yet Arrived—But Is Coming

Now we arrive at the present moment, and here is where the story becomes urgent and slightly unsettling. Everything I have described so far works well against classical computers. But quantum computers are different. They operate on principles so bizarre that they might as well be magic.

A regular computer processes information as ones and zeros. A quantum computer uses quantum bits, or qubits, which can be both one and zero simultaneously, a state called superposition. This allows quantum computers to explore multiple solution paths at once. For certain types of problems, this gives them enormous advantages.

Here is the terrifying part: the mathematical problems that protect your passwords, your financial information, and government secrets today are exactly the type that quantum computers could solve quickly. A sufficiently powerful quantum computer could, in principle, break the public-key encryption that secures nearly everything we rely on.

But there is hope. Cryptographers around the world are designing new encryption methods based on different mathematical problems. Some use lattice structures so complex that even quantum computers cannot solve them efficiently. Others rely on hash functions or error-correcting codes. These quantum-resistant algorithms are being tested, refined, and standardized right now.

Why should you care about this? Because if you send a secret message today that needs to remain secret for the next 30 years, and a quantum computer breaks your current encryption in the next 10 years, your secret is no longer secure. Governments and organizations are already updating their systems to prepare for this future.

Quantum cryptography takes a different approach entirely. Instead of relying on mathematical difficulty, it uses the laws of physics itself. Information is encoded in individual photons, particles of light. The moment someone tries to observe or tamper with these photons, they change, alerting both sender and receiver to the eavesdropping attempt. This is not a matter of computer power or cleverness. It is a consequence of how the universe actually works. This makes quantum key distribution theoretically unbreakable, though it remains technically challenging and expensive to implement.

The history of cryptography shows us that every shield eventually faces a sharper sword. But it also shows that humans are remarkably good at forging new shields just in time. The work happening now in quantum-resistant cryptography and quantum key distribution represents the latest chapter in an ancient struggle. It is a reminder that security is not a destination but a continuous process of innovation and adaptation.

As you navigate your digital life, you are trusting systems that represent centuries of intellectual effort, wartime ingenuity, and forward-thinking research. The secrets you send through the internet are protected by mathematics so elegant that it bordered on the impossible to discover. That alone makes the story worth knowing.